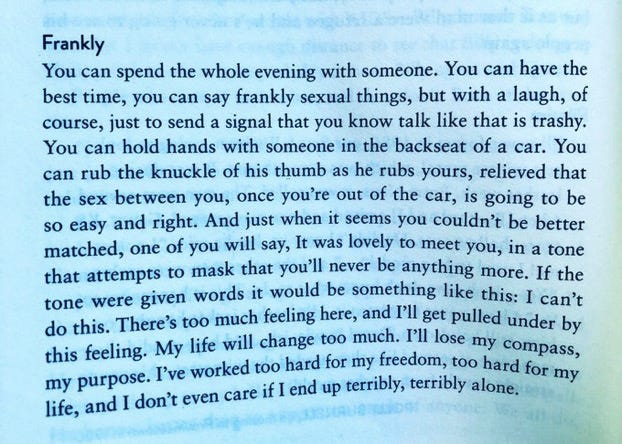

002: Drowning In It

— Paul Lisicky, Later: My Life at the Edge of the World

I have always wanted to be ruined by love. It is why, upon reading this (the first time, and every time after that) it felt like Paul Lisicky himself punched me in the gut. Not because I related to it but precisely the opposite: I knew myself to be someone who, in the fury of a love that came fast and hard, wanted to be pulled under by this feeling. And I was. And my life changed too much. And I lost my compass, and I lost my purpose. And indeed, my freedom and my life that I had worked too hard for, was so easily thrown away. In the wake of burgeoning love, I tossed a lot of shit aside.

I don't know what it is to fear being subsumed so much that at some point it becomes indistinguishable from self-abandonment. When I gave myself to dreams—his, my own—it was not without the understanding that becoming someone else's fantasy necessitated my own death. When told that love was a shapeless and undefinable thing, so formless as to be invisible, so invisible it makes you wonder if it's even there, I was asked to step blind, with him, to a place that was drowning in it.

And so I drowned. I wanted to. In the Atlantic ocean, a year and six days ago today. And it was only through this way I erased myself that I could become something else, a vessel for someone else's desires, waiting to be filled. And I wonder if in my recklessness was the unfounded faith in the actual impossibility of death, of injury; that I found myself to be so truly immune or invincible that I needed to be that much closer to erasure to know I was, indeed, still here.

Fantasy is compelling because even when you are someone else's, the fantasy of who you are is entirely yours. It is unclear even when you build a fantasy with someone else that their version comes close to yours. In many ways it’s the only way the fantasy works: that the world being lived in by both people is actually not one world but two, and that the illusion is that they’re crafting it together but in reality, they’re hardly contingent on each other at all.

In M. Butterfly, David Henry Hwang writes, "the man who catches a butterfly will pierce its heart with a needle, then leave it to perish. I began to wonder: had I too, caught a butterfly who would writhe on a needle?"

The thing about Butterfly is, after all, that she dies for ruinous love. She buries herself in layers only to empty herself out. She dies under the gaze of a man who never truly sees her, and never really wants to. This is a particular kind of annihilation: one that we do entirely to ourselves. At some point we must admit that it is not an act that robs us of our agency; in fact, it is one that necessitates it. When did blindness become something we were so willing to throw ourselves into? When we render ourselves as pure fantasy, how quickly do we forget that we have bodies to be cared for, with lives to have stake in?

There is a lot here about desire, the cost of buying into delusion, the way we hollow ourselves out for a fantasy we know is not true. I increasingly think that so much about how we fall in love is about our projection of our greatest longings and deepest demons onto someone we barely, and maybe can never really, know. Maybe all love is fantasy. And in these fictions we would rather live in, where the rules are different, devotion carries a gravity so heavy it could destroy you. In the trappings of a world so brilliant, what happens when you’re confronted with the glimmers of something wicked? When the illusion starts to slip, will we renounce ourselves to stay there forever? ✦